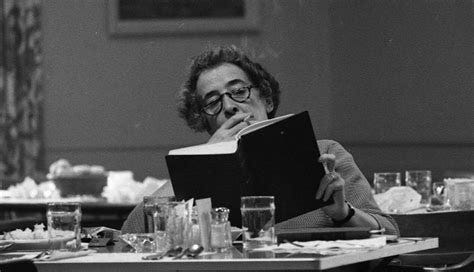

Hannah Arendt, one of the most significant political philosophers of the 20th century, offered a chilling analysis of the nature of evil in her concept of the “banality of evil.” She argued that great atrocities are often committed not by monsters, but by ordinary people who cease to think critically about their actions, simply following orders or blending into a crowd without moral reflection. Her work has become an enduring reminder of how power structures can corrupt, and how easily individuals can become complicit in wrongdoing when they fail to question authority.

The relevance of Arendt’s ideas is striking when we reflect on the events of January 6, 2021. As many Trump supporters gathered to protest what they believed to be a stolen election, the day spiraled into a scene of chaos that has since become a flashpoint in American political discourse. But beneath the headlines of insurrection, another layer has emerged, raising questions about how that day unfolded and who exactly was involved.

Reports have surfaced suggesting that undercover agents—some embedded as Trump supporters—were among the crowd, including CHA operatives tasked with monitoring the situation. These revelations raise complex issues about the roles that authority and manipulation played on that day. Were these agents simply observing the crowd, or was their presence part of a broader strategy to influence or provoke certain behaviors?

In light of Arendt’s philosophy, we must ask whether these undercover operatives—and those who managed them—were functioning as cogs in a machine that blurred the line between protest and insurrection. Were they part of a larger attempt to stir unrest, relying on the crowd’s susceptibility to groupthink and the heat of the moment? If so, their involvement aligns disturbingly with Arendt’s warning that ordinary individuals can become tools of state power, following orders without critical thought.

Arendt’s work encourages us to think deeply about our own roles in society and the structures of power that we interact with. Whether we’re considering the actions of citizens or the maneuvers of government agencies, the importance of individual responsibility and moral reflection cannot be overstated. It’s too easy for anyone, whether a protester or an operative, to become part of a larger force that leads to destruction, not through active malice, but through a passive acceptance of orders or a lack of critical engagement.

January 6th will undoubtedly be studied and debated for years to come, but one thing is clear: it wasn’t just a moment of chaos driven by angry citizens. It was also a reflection of how power structures can manipulate and influence events in ways that aren’t always visible to the public. And in that manipulation lies a deeper moral question—one that Arendt would compel us to face.

The lessons from Arendt’s philosophy are clear: we must remain vigilant, think critically about our actions, and question the roles that authority and power play in shaping our behavior. If we fail to do so, we risk becoming participants in the very systems we believe we are resisting.